Alan J. Pakula's Paranoia Trilogy

A thematic trilogy that serves as a snapshot of the paranoia present in the early 70s

Thematic trilogies fascinate me. They’re the distillation of an idea or theme that a director, consciously or not, gets to investigate in three different iterations. They’re unique case studies, especially considering how most thematic trilogies aren’t purposefully made. The act of grouping these unrelated films under a common theme is done retroactively by critics, historians, or fans and the resulting trilogy is often a reflection as to what the crews behind these films are interested in making at the time. It’s no surprise that these three Pakula films, all made in the early 1970s, paranoia is a common theme. Klute, in 1971, was on the heels of the turbulent and political unrest of the late 60s. The influence of Robert Kennedy’s assassination can be seen in every facet of the Parallax View. And Watergate, the scandal overshadowing the release of those two films becomes the subject of All the President’s Men, the final film in the trilogy. These three movies reflect the cultural zeitgeist and fear that people had. Of unknown and unseen manipulators in the shadows, plotting conspiracies, and sowing mistrust.

Alan J. Pakula isn’t an oft-talked-about director, which is a disservice considering his vast career. He started as a producer before directing his first feature, The Sterile Cuckoo in 1969. Three of his next four succeeding films became his paranoia trilogy. Despite the critical acclaim many of his films have, his impact and legacy are less well-known than other established directors. The other main creative that worked on this trilogy (and many of Pakula’s other films) was Gordon Willis, the cinematographer, who also was the DP for the Godfather films and helped define how films looked in the 70s. An emphasis on stark shadows and straight lines. The two shaped the look of each of these films as they take in vastly different places from the cramped lodgings of New York City to the corporate buildings of Los Angeles, to the newsrooms of Washington D.C.

So let’s get into it.

Klute

Klute tells the story of John Klute, played by Donald Sutherland, a small-town investigator who heads to New York City to investigate the disappearance of a friend of Klute’s whose last known contact was with a call girl, Bree Daniels, played by Jane Fonda.

Though she’s not the title character, Jane Fonda is the star of this film. In part due to her complex performance of Bree and in part because the story is literally about her. She’s the focus of the film. By the time Klute contacts her, some thirty minutes in, we’ve already become intimately familiar with Bree’s life as she picks up johns and gets rejected from casting calls. It helps that Pakula is an actor’s director. Three stars of his films: Jane Fonda, Meryl Street, and Jason Robards, all won Oscars for their performances in Klute, Sophie’s Choice, and All the President’s Men respectively. Pakula has said himself that actors know their characters better than he does and to trust their instincts, which is obvious from Fonda’s performance. The scenes between Bree and her therapist are all improvised and show just how much depth Jane Fonda has to her character. These scenes get to the emotional heart of who Bree is.

Bree defines the plot and pushes the story forward. The screenwriters and Pakula defined the film as a “character study that uses melodrama to explore that character.” Bree, due to the nature of her work, doesn’t get close to her clients and her views on love and relationships are a result of that. She keeps her distance from intimate relationships, liking the control and independence that position grants her. When Klute enters the pictures and they begin to work together more and more, those feelings on relationships begin to get complicated as she develops feelings for Klute. He almost plays the part of an antagonist for Bree, forcing her to examine a part of herself that she doesn’t want to. Their relationship is one of opposites. Bree is the independent free-spirit while Klute’s repressed and button-upped. By being forced to work together, they begin to have an affinity for each other. Klute enters New York City from his quiet life in a small town expecting the city to be full of sin and he does encounter some in terms of pimps and drug dealers. His initial assumptions about Bree are similar and his feelings for her surprise him. They’re both scared of their own feelings for different reasons, but are still drawn to each other, and force them to look at themselves in new ways. That fear erupts towards the end of the film leading to a climax that feels inevitable.

And when Klute’s called a character study in the guise of a melodrama, that’s right on the money. The actual investigation feels perfunctory. A necessary facet to talk about the characters. The movie reveals the culprit multiple times throughout the film and I didn’t realize the first few times because it was so unexpected to me. To reveal the source of the mystery so early. But it still works. Bree and Klute are compelling enough on their own that their interactions fuel the film forward. The climax even keeps this idea, with most of the scene being dedicated to Bree’s character and aforceful look in the mirror for her. Bree and Klute both uncover truths about themselves by the end of the film, yet Bree’s last lines make it starkly clear that anything is still possible. As they leave New York together, it’s clear that their changes may only be temporary.

The Parallax View

The Parallax View follows Joe Frady, played by Warren Beatty, a newspaper reporter who investigates a conspiracy after witnesses of a senator’s assassination years before start turning up dead.

The film has similar qualities to other 70s conspiracy films like Three Days of the Condor or Marathon Man. That of an unknown, oppressive, and powerful entity (often something governmental or corporate) that once you know where to look, has its fingers everywhere. And in another opposite choice from Klute, this ain’t no character study. We don’t learn much about Frady. There are hints at a past obsessiveness over the senator’s assassination that opens the film, and Frady definitely follows the rabbit hole even when his life is in danger, but he’s also fueled by an equally strong motivation: guilt. A fellow reporter and ex-girlfriend of Frady’s comes to him for help when she fears her life is in danger. He assures her that’s not the case but she’s found dead shortly after. These early scenes give us a taste of Frady’s character but once the action starts that’s pushed to the side. Instead, Frady embodies the reporter stereotype in the wake of Woodward and Bernstein. Someone who puts the truth above all else, even their own lives. Counter-culture. Doesn’t put up with authority. And you know they’ve got to have a chief editor that acts as a mentor. It’s all there.

What surprised me most about The Parallax View was how much action there was. There’s the opening assassination that takes place on the roof of the Space Needle of all places. In the first thirty minutes, there’s an attempt on Frady’s life, a white water rapid ride, and a destructive car chase. Frady straight-up kills a dude. In self-defense, granted, but it’s a shocking start to the second act that turns that action into tension.

It feels like Frady is uncovering the kind of conspiracy that grew in people’s minds in the aftermath of JFK (Robert Kennedy’s assassination inspires the film’s opening). The film refrains from making any real-life comparisons to those tragedies. Yet it feels like a conspiracy out of control, full of ludicrous theories and a rabbit hole that goes deeper and deeper. It posits a world where a conspiracy theory actually exists and Frady is the only one getting to the bottom of it. It’s cathartic. Throughout the film Frady is shot from afar, often alone, and looks like an oppressed speck in the frame, with the weight of the world surrounding him. Shots are held for longer than necessary, often to induce tension, and force the audience into the role of an observer.

Halfway through the film, Frady discovers the Parallax Corporation, a group that looks for people with antisocial personalities and possibly turns them into assassins. Frady cheats his way in and is subjected to a six minute presentation. It’s a brilliantly edited sequence of still images with music that pairs violent imagery with positive words and emotions. We don’t see Frady’s reaction during the presentation. Instead, it’s presented to us, the audience, in a frenetic barrage of stimuli. It’s hypnotic and shocking and marks a stark change between the action of the first half of the film with the tense, overwhelming paranoia of the second half.

SPOILERS

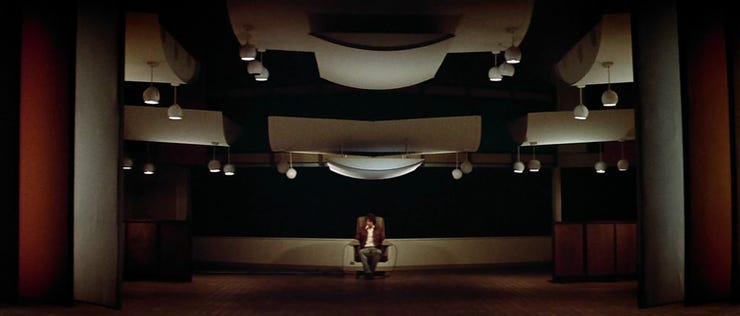

It’s difficult to talk about this film without spoiling the ending so I encourage you to watch the film first. After the multiple near collisions with death Frady endures, he tails a member of the Parallax corporation to an auditorium that’s rehearsing for an upcoming rally for a senator. Frady witnesses the senator’s assassination from the catwalks and then realizes that he’s being set up as a patsy. As he attempts to escape, he’s killed by the real assassin. The film ends with the press release that Frady was a frenzied assassin acting alone.

The ending is a sucker punch. Frady’s persistence and dedication seem admirable, all for it to crash and burn at the end. It supposes that conspiracies are conspiracies for a reason. If the conspiracy shown in the film was real, what are the chances that one man could conquer it? It’s a realistic take. That one person probably can’t change the world and fight back against a group whose purpose is to stay hidden.

And that leads to...

All the President’s Men

The newspaper movie incarnate. The story of Watergate, Woodstein, and Nixon’s resignation.

A brief synopsis for those who don't know. Two reporters, Woodward and Bernstein are assigned to report on a break-in at the Democratic National Committee offices and uncover a conspiracy reaching the President of the United States.

The fact that this movie works shocks me. Granted, my knowledge of these events is cursory, but this film came out in 1976, four years after the actual Watergate scandal took place. Audiences at the time fully knew the events of the film and how they resolved. It’s not like this movie was telling an unknown story. And apparently, the solution of how to tell a story that everyone knew was to get so specific with everything. To get into the minutia of reporting. Collecting evidence, connecting threads, and getting witnesses to talk. The process of news reporting may be dramatized but is shown in all of its frustrating glory.

A lot of that comes from basic rules of conflict. Someone wants something, there’s an obstacle in their way, and they need to get it now. The actual actions of going through library slips or tracking down CREEP employees seem like they’d be boring, but because of the inherent conflict in those actions, it works. It’s compelling. Even our understanding of how the story ends works in our favor as it gives us an understanding of the overall stakes. Stakes that the characters aren’t even fully aware of yet.

The depth of information and connections that Woodward and Bernstein uncover was overwhelming for me, especially without previous knowledge. It took me a while to put together that CREEP stood for Committee to Re-Elect the President and wasn’t some secondary shell corporation. It reminded me of film noir plots where there’s so much complexity and so many secondary characters that a rewatch is often needed to make sense of things. All the slush fund controllers that Woodward and Bernstein are trying to get the names of are never shown on screen, and if they are, not in a meaningful way that I remembered. Sometimes they’re just a voice on a phone. Nixon is only ever seen through real-life news broadcasts. And yet the same can be said for Woodward and Bernstein. We don’t learn much about them as characters, only picking up details from their actions and how they pursue leads. On one hand, it’s the most clear-cut example of showing character (actions do speak louder than words), on the other hand, we only learn about their personalities, not anything deeper.

The film manages to turn shots of work being done in the newsroom cinematic. One shot that’s about five minutes in length is a split-diopter shot of Woodward following a lead and making numerous phone calls while on the opposite side of the newsroom, reporters watch a news broadcast about Eagleton stepping down. It’s engrossing, literally pulling us into Woodward’s work with a slow zoom. The film uses these news broadcasts, some seen, some heard, to showcase the ’72 election as the election cycle moves forward, giving us a rudimentary timeline.

The climax is where things get interesting because I’m not sure there is one. The story builds to Woodward and Bernstein publishing the names of the five slush fund controllers, but flub one of the sources. They’re told by their informant, Deep Throat, that their lives are in danger, their editor tells them to keep working on the story, and then the movie kinda ends. It’s an invigorating final shot, of Woodward and Bernstein continuing to work through their mistake while Nixon gets sworn in for his second term. The only catharsis to the film’s entire buildup is a series of typewriter bulletins detailing the aftermath of the film’s events. It’s a letdown but doesn’t ruin the film, ending with an implication that the truth will eventually come out. A stark contrast to The Parallax View’s ending. Of these three films, All the President’s Men is the most optimistic. Possibly because of its real-life origins. The story of an actual conspiracy resolved.

This entire trilogy is a fascinating case study, reacting and responding to the paranoia of the time they were made in. And it’s no surprise that the ambiguous final words of Klute and the straight downer ending to The Parallax View gave way to the still vague, but optimistic ending of All the President’s Men. These three films are a cultural and historic snapshot. A snapshot of fear, paranoia, and truth during a tumultuous time and shows a growth, that regardless of how impossible the odds feel, how ever-present the threat is, that the world may have some hope in it after all.